- This is a section extracted from the thesis cited below:

Citation:

Zidian Guo, Ketong Li, June 2025, 6th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in HCI (AI-HCI), Part of HCI International Conference, Gothenburg, Sweden

At a Glance

- Interference

- Distraction as an Additional Visual Input.

- Impact on Ear-Voice Span.

- Overreliance

- Error Propagation

- Underperformance in Response to System Failure

- Insufficient Support for Interpreters’ Needs

1. Interference

1.1 Distraction as an Additional Visual Input.

One of the primary limitations of current Computer-Aided Interpretation (CAI) tools is their tendency to create distractions. The additional layers of visual input introduced by CAI tools impact both Reception and Human-machine Interaction (HMI) effort. Interpreters rely on multiple sensory inputs beyond the spoken word. They actively process a wide range of contextual cues, such as the speaker’s tone, gestures, facial expressions, audience reactions, their own notes, and the slide decks presented on a different screen. Using CAI tools is introducing multiple extra visual inputs into an already complex environment. As interpreters continuously coordinate memory, production, and self-monitoring, additional visual demands can become counterproductive, diverting their attention away from their core task rather than enhancing their performance.

Machine-generated suggestions often trigger an immediate shift in attention, regardless of whether the interpreters actively seek assistance from the tool.

In multiple controlled experiments with minimal visual stimuli, participants with different levels of expertise consistently gravitate toward visual suggestions provided by CAI tools. Across different interpretation modalities and UI designs, the presence of ASR transcripts [7, 10, 12], numerical or term suggestions [8, 9], or machine translation [13] captures participants’ attention as soon as the suggestions appear. Moreover, this redirection of attention appears to be quite indiscriminate. Participants equally consult CAI visual suggestions regardless of the accuracy of the ASR transcripts [7] or the complexity of the problem triggers, such as the term’s length [8] or the magnitude of numbers [10].

Considering that most current ASR tools provide suggestions non-selectively, such as imprecise transcripts once utterance is recognized, or numericals and terms solely based on ASR transcription and rule-based matching with a termbase, there is a risk that the combination of non-selective suggestions of CAI tools and interpreters’ immediate and indiscriminate attention to them will increase unnecessary cognitive demand or, worse, impact the overall quality of interpretation.

Moreover, it is worth noting that the cognitive competition among multiple visual inputs, a common case in real interpretation settings, is largely overlooked in experiments. In previous studies, participants were presented with either ASR alongside a video of the speaker [7], units of interest with video of the speaker [9], or only ASR prompts with numbers highlighted [10]. These controlled experimental settings spare participants of the real-life challenge of deciding what visual cues to prioritize, reducing the choices to two: focusing on CAI suggestions or a video. To the best of our knowledge, no existing experiment has attempted to simulate settings with more than two competing visual inputs to examine how performance is affected when interpreters must allocate cognitive resources to choose and switch between different visual layers. For instance, they may struggle to look up a term in the glossary when it’s not extracted by CAI tools, or overlook other critical visual cues due to the automatic redirection of attention toward machine suggestions when they appear.

1.2 Impact on Ear-Voice Span.

CAI tools have shown significant impact on interpreters’ Ear Voice Span (EVS), the time lag between the speaker’s utterance and the interpreter’s rendition in SI. Across language combinations, most researchers agree on an average EVS range of 2 to 4 seconds, while some studies recorded as high as 10 seconds [14].

EVS can be seen as the temporal representation of the cognitive process in SI, indicating an interpreter’s dynamic decision-making when presented with limited information.

◼ A longer EVS is typically opted for when the existing segment lacks sufficient context for production. However, excessive lag increases the risk of falling too far behind the speaker, which can lead to cognitive overload as long segments accumulate in working memory.

◼ A shorter EVS lowers burden for working memory but may induce literal or myopic interpretation that sacrifices contextual coherence. Thus, EVS must remain dynamic with each meaning unit.

However, research suggests that interpreters interacting with CAI tools tend to adjust their EVS to the suggestions’ latency.

This adaptation manifests in both ways: Interpreters may increase their EVS to wait and consult machine suggestions, even when they already know the correct rendition [8]. Conversely, they may shorten their EVS to prematurely use a half-formed or erroneous suggestion on screen when prompted [10]. Rather than optimizing the workflow, this machine-driven pacing forces interpreters into an artificial rhythm, which leads to a significant increase of disfluencies such as backtracking, fillers, and pauses [6]. Additionally, this interference introduces new risks of error propagation, and cascading failures when the suggestions do not appear as expected. These issues will be further elaborated in Section 2.2.

EVS in SI with CAI tools is also influenced by the different speeds at which interpreters process auditory and written visual inputs, compounded by the unstable latency of ASR used in these designs.

The introduction of CAI systems as a visual aid does not automatically enhance concentration on listening or comprehension.

Instead, it requires greater coordination efforts to monitor and match written input with audio. For instance, if an interpreter reads at a slower pace than they listen, a phenomenon observed by comparative studies between SI and sight translation [15], the start of production may be dictated by the time required to process the visual suggestions. Even under optimal ASR latency, this delay can lead to an increase of EVS.

Live ASR transcript readability significantly impacts how interpreters process information while switching between visual inputs. When redirecting their attention to ASR transcripts, interpreters need to first identify the segment of interest in the running transcript before they can process the information.

This process can be further complicated by the low readability of the ASR solution commonly used in CAI tools to minimize latency. Most of them rely on the first-pass output of a two-pass ASR system, such as Google Speech-to-text (STT) and Microsoft Azure, which are typically based on Listen-Attend-Spell (LAS) or Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs). Interpreters therefore are forced to work with approximate, unedited or even actively back-editing ASR transcripts that lack proper syntactic segmentation, punctuation, and capitalization, a frequent complaint in interpreters’ usability research [8, 10].

The issue becomes more pronounced when the speech is complex. For instance, when tested with a fast impromptu speech in a slight German accent, InterpreterBank ASR, which relied on provisional Google STT results [10], produced four chunks of run-on text for a 12-sentence segment, with misparsed phrases, no punctuation, and arbitrary capitalization (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. A first-pass ASR transcript for a fast and accented speech in InterpretBank ASR [18]

2. Overreliance

2.1 Error Propagation

In theory, interpreters are able to strategically leverage machine suggestions, utilizing their support while applying human judgment to correct errors and refine the output.

However, in practice, the presence of CAI-generated output can introduce overreliance and new risks of error propagation. This issue is particularly prevalent in complex SI tasks with multiple problem triggers, such as

- high speech rates,

- poor sound quality,

- technical terminologies,

- or complex grammatical structures.

Unfortunately, these are also the conditions under which live ASR tends to underperform, which means that CAI systems may be the least reliable precisely when interpreters need them most.

At the same time, interpreters are most susceptible to machine’s errors in these scenarios, as they have less cognitive capacity to validate the ASR output before incorporating it into their rendition.

Both Prandi and Defrancq note that overreliance on CAI leads interpreters to copy errors in the transcripts without realizing it, even deeming the tool helpful in their rendition [9,10]. Similarly, research shows that participants copy errors in 25% of cases when ASR was imprecise [7], and that visual information incongruent with audio input impedes accuracy [16].

◼ As a result, instead of acting as a fail-safe mechanism, CAI systems can become a source of compounded errors, particularly when the interpreter’s cognitive load is already near saturation. More critically, this overreliance contradicts professional interpretation standards, which require interpreters to prioritize auditory input over visual cues in cases of incongruence [16].

The propagation of errors in machine suggestions also affects other aspects of production, including

- flexibility,

- fluency,

- and information prioritization.

Compared to audio input, visual input may exert greater interference, increasing the likelihood of misuse of interlingual homographs or literal translations, a common challenge in sight translation [15].

Additionally, ASR support may exacerbate disfluency and stylistic errors, as interpreters adjust their EVS in the attempt to wait for or catch up with the ASR output, as established in Section 2.1. This often results in unwanted pauses or false-starts [6]. Interpreters also tend to prioritize interpreting CAI suggestions over other acoustic-only information, leading to omission and misinterpretation of challenging segments not supported by CAI systems [6].

These findings highlight a critical challenge in CAI tool usability:

while designed to enhance interpretation accuracy, these tools may inadvertently encourage interpreters to overrely on automated outputs without sufficient critical evaluation.

This creates a paradox in which tools designed to assist in quality assurance may instead introduce new risks, compromising the reliability of the final output.

2.2 Underperformance in Response to System Failure

Apart from error propagation, interpreters may feel disoriented when CAI support fails to function as expected. This is the unfortunate consequence of the common user perception of CAI tools as a safety net reported in various studies [8, 10]. While the tools can boost confidence and by extension accuracy serving as the backup,

it can also induce blind trust and become a crutch that weakens independent decision-making.

Studies show that performance drops below baseline (i.e performance in SI without CAI tools) when participants suddenly lose support from the tool [10]. More than half of the participants omitted a unit of interest when the CAI tool omitted it, and terms not showing up as expected was rated as the most significant distraction affecting CAI usability in the qualitative feedback [8]

Overreliance on CAI tools can alter interpreters’ strategies and impact performance. As mentioned in Section 2.1, CAI tools as additional visual inputs often dominate interpreters’ attention and add demand for Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) efforts.

When interpreters expect CAI assistance, they are

- less likely to write down numbers,

- manually lookup terms in the glossary,

- or signal their boothmate for help.

If such expectation fails to materialize, they are left with limited alternative support (e.g. notes, lookup results) to recover the unprovided information. The time available to restrategize will be further constrained by the waiting period for the suggestion and the time taken to register that the suggestion is erroneous or that it is not showing.

Under time pressure and lack of options, interpreters are more likely to either omit or misinterpret the unit of interest [8,9] instead of reaching for other strategies to interpret with less severe inaccuracy, such as approximating, using superordinates, or paraphrasing [1]. When, if at all, such strategies are deployed, there can be spillover effects on subsequent segments as EVS expands.

Admittedly, participants in previous studies were often tasked to interpret without preparation on the topics of the speeches [6, 7, 10], which may explain the over-expectation that anything they were unsure of would be suggested by the systems. Preparing and reviewing the glossary before an assignment can help interpreters align their expectations better to what CAI tools can provide and potentially reduce overreliance.

However, two major issues persist.

◼ First, if future systems continue to rely on a low-precision first-pass ASR transcript to match units of interest, the inevitable CAI omissions and errors will remain a hindrance.

◼ Second, if future CAI systems are to leverage machine capabilities to store and search automatically in large databases, such as domain-specific corpora, or apply machine learning to predict units of interest [17], there will be still cases where information does not appear as expected as interpreters will not be able to exhaust the database during preparation.

As long as these conditions remain, it is safe to recommend that CAI tools must be built upon accurate ASR systems that allow integration of redundancy mechanisms to minimize distraction and provide alternatives when auto-matching fails. Such mechanisms may include allowing manual search in the termbase or a spotlight search in the transcript.

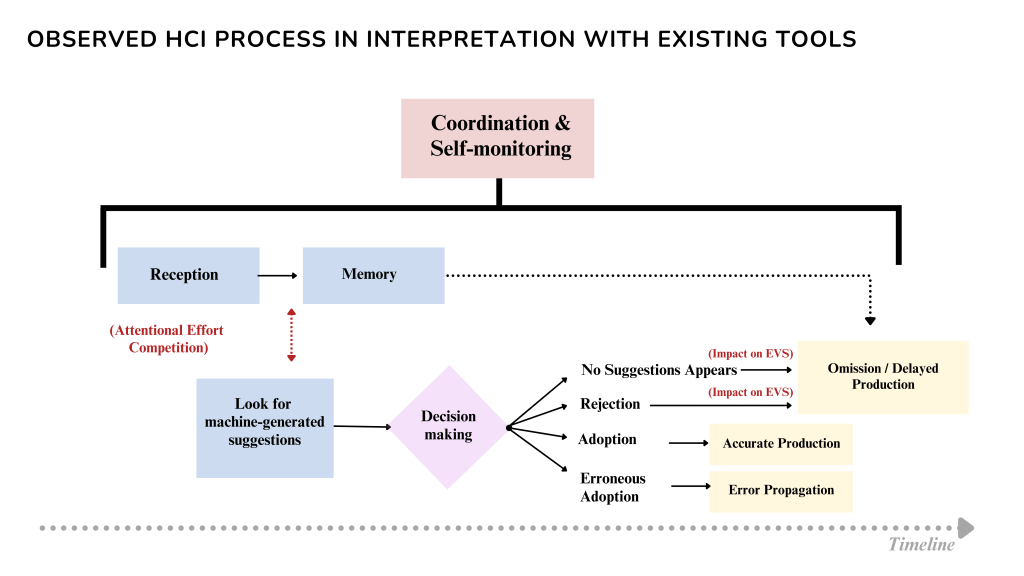

With that in mind, the observed interaction between interpreters and existing CAI tools during SI can be understood through as follows (see Fig.3):

When the interpreter receives a unit of interest in the source speech, they will be prompted by CAI tools to immediate look for, and if available, look at machine-generated suggestions. This checking process competes for attentional effort with the reception of other layers of visual inputs and the reception of subsequent information.

Then, the interpreter must quickly assess the validity of the suggestion and decide whether to accept or reject it.

Depending on the decision, they might use the suggestion to produce an accurate interpretation, propagate the erroneous suggestion unknowingly, omit the information, or restrategize to produce interpretation with a prolonged EVS when the tool fails to provide a suggestion.

3. Insufficient Support for Interpreters’ Needs

The unconscious tendency to prioritize technological capabilities over human needs in CAI design often leads to features that fail to address interpreters’ actual challenges.

For example, existing terminology extraction features listed many high-frequency words (see Fig.4), which are typically not considered “terminology” for professional interpreters; they are commonly recognized, require no preparation, and add unnecessary clutter to the system’s output. In terminology management, such extractions are often regarded as “noise”, requiring interpreters to manually delete and refine the generated word lists into usable glossaries. The inability of the system to identify and prioritize these critical low-frequency terms limits its usefulness, as it fails to address the real challenges interpreters face in their work.

Fig. 4. Screenshot of the first page of glossaries generated by InterpretBank Confidential AI (left) and Cloud AI (right) from two advanced English texts [19][20], sorted alphabetically

Another example is the word-to-word translation feature that provides machine translation when interpreters click on a word in the interface (see Fig.5). The fundamental assumption behind this functionality, that interpreters can immediately use machine translations, overlooks a critical flaw: if an interpreter does not already know the term, they also likely lack the ability to verify its validity.

A more human-centered approach would involve providing interpreters with additional contextual information alongside machine translations, such as supplying hypernyms or a brief definition, so as to give interpreters a basis to assess its accuracy. For example, rather than merely displaying a translation for a term, the system could indicate that it refers to a chemical compound, a pharmaceutical drug, or an organization, etc..

Even a small clarification would inform interpreters with a general sense of the term’s meaning, allowing them to make a sounder judgment about whether the translation aligns with the given context. A short definition will also provide more flexibility in rendition should the interpreter opt for safer strategies such as approximation and generalization instead of directly adopting the machine translation.

Fig. 5. Screenshot of a non-context-aware machine translation suggestion in InterpretBank ASR, incorrectly rendering “addressing” as “寻址” (finding the address).

References

- Gile, D.: Basic Concepts and Models for Interpreter and Translator Training. Benjamins, Amsterdam, 197–199 (1995).

- Gile, D.: Testing the effort models’ tightrope hypothesis in simultaneous interpreting: A contribution. HERMES: Journal of Language and Communication in Business 23, 153–172 (1999). https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v12i23.25553.

- Kalina, S.: Quality assurance for interpreting processes. Meta: Journal des traducteurs 50, 768 (2005). https://doi.org/10.7202/011017ar.

- Fantinuoli, C.: Speech Recognition in the Interpreter Workstation. Translating and the Computer, London (2017).

- Gile, D.: The Effort Models of Interpreting as a Didactic Construct. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-2070-6_7 (2021).

- Rodriguez Gonzalez, E.: The use of automatic speech recognition in cloud-based remote simultaneous interpreting. Doctoral Thesis, University of Surrey (2024).

- Li, T., Chmiel, A.: Automatic subtitles increase accuracy and decrease cognitive load in simultaneous interpreting. Interpreting 26(2), 253–281 (2024).

- Frittella, F. M.: Usability research for interpreter-centred technology: The case study of SmarTerp. Translation and Multilingual Natural Language Processing 21. Language Science Press, Berlin (2023).

- Prandi, B.: Computer-Assisted Simultaneous Interpreting: A cognitive-experimental study on terminology. https://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/348, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7143056 (2023).

- Defrancq, B., Fantinuoli, C.: Automatic speech recognition in the booth: Assessment of system performance, interpreters’ performances, and interactions in the context of numbers. Target 33 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1075/target.19166.def.

- Pisani, E., Fantinuoli, C.: Measuring the impact of automatic speech recognition on number rendition in simultaneous interpreting. (2021).

- Wang, X., Wang, B., Yuan, L.: The function of ASR-generated live transcription in simultaneous interpreting: trainee interpreters’ perceptions from post-task interviews. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 12, Article 166 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04492-w.

- Chen, S., Kruger, J.-L.: The effectiveness of computer-assisted interpreting: A preliminary study based on English-Chinese consecutive interpreting. Translation and Interpreting Studies. The Journal of the American Translation and Interpreting Studies Association 18(3), 399–420 (2023).

- Janikowski, P., Chmiel, A.: Ear–voice span in simultaneous interpreting: Text-specific factors, interpreter-specific factors, and individual variation. Interpreting (2025). https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.00116.jan.

- Chmiel, A., Janikowski, P., & Cieślewicz, A. (2020). The eye or the ear? Source language interference in sight translation and simultaneous interpreting. Interpreting, 22(2), 187–210. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.00043.chm

- Chmiel, A., Janikowski, P., Lijewska, A.: Multimodal processing in simultaneous interpreting with text: Interpreters focus more on the visual than the auditory modality. Target 32(1), 37–58 (2020).

- Vogler, N., Stewart, C., Neubig, G.: Lost in Interpretation: Predicting Untranslated Terminology in Simultaneous Interpretation. Proc. NAACL-HLT 2019, 109–118 (2019).

- Asia Society: STATE OF ASIA 2023: Peak China or New China? (2023). https://www.youtube.com/v=eJizj0W9wkY

- Bolton, J.R.: Chapter 1: The Long March to a West Wing Corner Office. In: The Room Where It Happened. Simon & Schuster, New York, pp. 1–42 (2020).

- Lewis, S.: The United Nations and Gender: Has Anything Gone Right? Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, New York (2009).

- Pöchhacker, F., Liu, M.: Interpreting technologized: Distance and assistance. Interpreting26(2), 157–177 (2024).